Elul is similar to the word “Search” in Aramaic and is the perfect way to describe the season of Teshuvah leading us to Tashlich and Mikveh.

But what does that even mean?

Traditionally, people all over the world prepare for the New Year on Yom Teruah with the blasting of the shofar filling the air every day and the cacophony of blasts during the feast. This explosion of sound is then followed by the solemnity of the 10 Days of Awe leading to Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement.

Elul is marked by a focus on righting wrongs and resolving elements of relationship distresses caused or experienced in the previous year or years. It is a time of returning to the Lord and to each other. In a sense, it is an emotional and spiritual reset.

Everyone knows we can’t repent of things of which we are ignorant and, in those areas, our hope is for the Ruach HaKodesh to lead us and for the blood of Yeshua to cover our lack of insight or knowledge.

However, if you are a fellow human, we are aware we all have plenty of ways we have fallen short. Teshuvah is taking the initiative to create a focused time to take those records of wrong and wipe the slate clean on both personal and spiritual levels.

As a Hebrew word that has come to mean repentance, teshuvah literally means “return”. In Judaism, this means it has become an element in the atoning for sin. As believers in Yeshua, we know there is only One who atones for our sin, so this repentance and returning isn’t about earning or achieving something we have already been freely given.

As believers seeking deeper relationship with each other and our God, repentance for the times we’ve missed the mark is integral to that growth. It is also a reflection of His love for us and of our love for Him. Taking this time during Elul (the month prior to Yom Teruah, which falls on Rosh Chodesh Tishrei) to evaluate ourselves while we spiritually clean house is not only a good idea it’s a biblical idea.

Yeshua, in Matthew 5, speaks clearly to the idea of reconciling and restoring relationships broken by disagreement, anger, bitterness, and judgment within His people. Matthew 5:23, “Therefore, if you are offering your gift at the altar and there remember that your brother or sister has something against you, leave your gift there in front of the altar. First, go and be reconciled to them; then come and offer your gift.”

When did people bring gifts to the altar?

Offerings and gifts were for the head of the month, Rosh Chodesh, at the beginning and culmination of vows, in gratitude for God’s provision and intervention, and, very specifically, on the High Holy Days, the biblical feasts.

The very core of Teshuvah through the actions of repenting or returning to those we love and those we are to be in community or fellowship with is integral to approaching God and prepares our hearts to follow Him in closer and deeper ways as we mature in our faith.

More than any other time of the year, as Yom Teruah brings in the Days of Awe and leads us toward Yom Kippur, our Day of Atonement, this is the season we eagerly prepare to be a beautiful bride, without spot or wrinkle, dressed in pure white, ready for our Bridegroom. The practice of Yom Kippur on an annual basis is a time of practicing for the wedding day to come. We want to be completely ready for Him without the hindrance of failed promises, regrets over poor behavior, or the hidden sins keeping us from boldly approaching Him with gratitude and confidence.

Now, we know we cannot make our selves righteous. However, we can be part of making ourselves ready.

Elul gives us time to examine and contemplate our condition. Seeking the Ruach and trusting Him to speak to us about how we should live and if there are those we have offended, those who have offended us, things which need to be made right so we can look ahead to the Days of Awe with joy and anticipation are a measure of Adonai’s grace and compassion as well as His unending patience with our fumbling faith.

So what are the Days of Awe? Dating back to 3rd venture BCE the recognition of this time period is attributed to Rabbi Yohanan and would have been part of Yeshua’s expression of the season as He celebrated within the community in Israel.

A famous poem, in Judaism, says there is a period between Yom Teruah and Yom Kippur where we can “avert the severe decree” through repentance, prayer, and charity. The requirements for repentance include a change of mind, a feeling of regret, and a determination to change, along with an effort to repair the effects of one’s misdeed(s).

10 is the biblical number of completion and has also come to symbolize responsibility and, as it correlates to the 10 Words (Commandments), is seen as a symbol of obedience and responsibility of God’s people toward His law.

Those 10 days, beyond Yom Teruah and aided by the deepening the focus and intensity of Teshuvah, give us a chance to prepare our to receive His blessing and walk with clear conscience as we step, more fully than ever before, into the beauty of His atonement for our sins and the hope of our eternal future with Him.

“The Ten Days of Repentance are seen as an opportunity for change. And since the extremes of complete righteousness and complete wickedness are few and far between, Rosh Hashanah functions, for the majority of people, as the opening of a trial that extends until Yom Kippur. It is an unusual trial. Most trials are intended to determine responsibility for past deeds. This one, however, has an added dimension: determining what can be done about future deeds. The Ten Days of Repentance are crucial to the outcome of the trial, since our verdict is determined both by our attitude toward our misdeeds and by our attempts to rectify them by changing ourselves.” ‘Rabbi Reuven Hammer.

Which leads us back to tashlich. An action directly related to Teshuvah and a symbolic gesture of casting bread as a representation of sins into a moving body of water. This tradition is reflective of Micah 7:19. As the prophet says, “He will take us back in love; He will cover up our iniquities. You will cast all their sins into the depths of the sea.”

Tashlich is not a biblical mandate but rather a practice that could have been done during the time of Yeshua.

Josephus refers to a decree the Halicarnassians made to permit the Jews to “Perform their holy rites according to the Jewish laws and have their places of prayer by the sea, according to the customs of their forefathers.” Some believe that this refers to the practice of tashlich. It is up for debate.

Here’s what we do know for sure. This did become a common practice in the 13th century so it’s at least been around that long.

Personally, I love the deliberate thoughtfulness of taking a piece of bread and, with each piece I tear off, taking the time to contemplate my heart, repent of the things the Ruach reveals to me, and cast those things physically away from me.

The cycle of Teshuvah and tashlich is one of repentance followed by a symbolic gesture of release while speaking a prayer of repentance and acknowledgment of YHVH’s compassion and kindness.

Which leads us to Mikveh. An action, when put in the right context, becomes a natural outflow of both repentance and prayer.

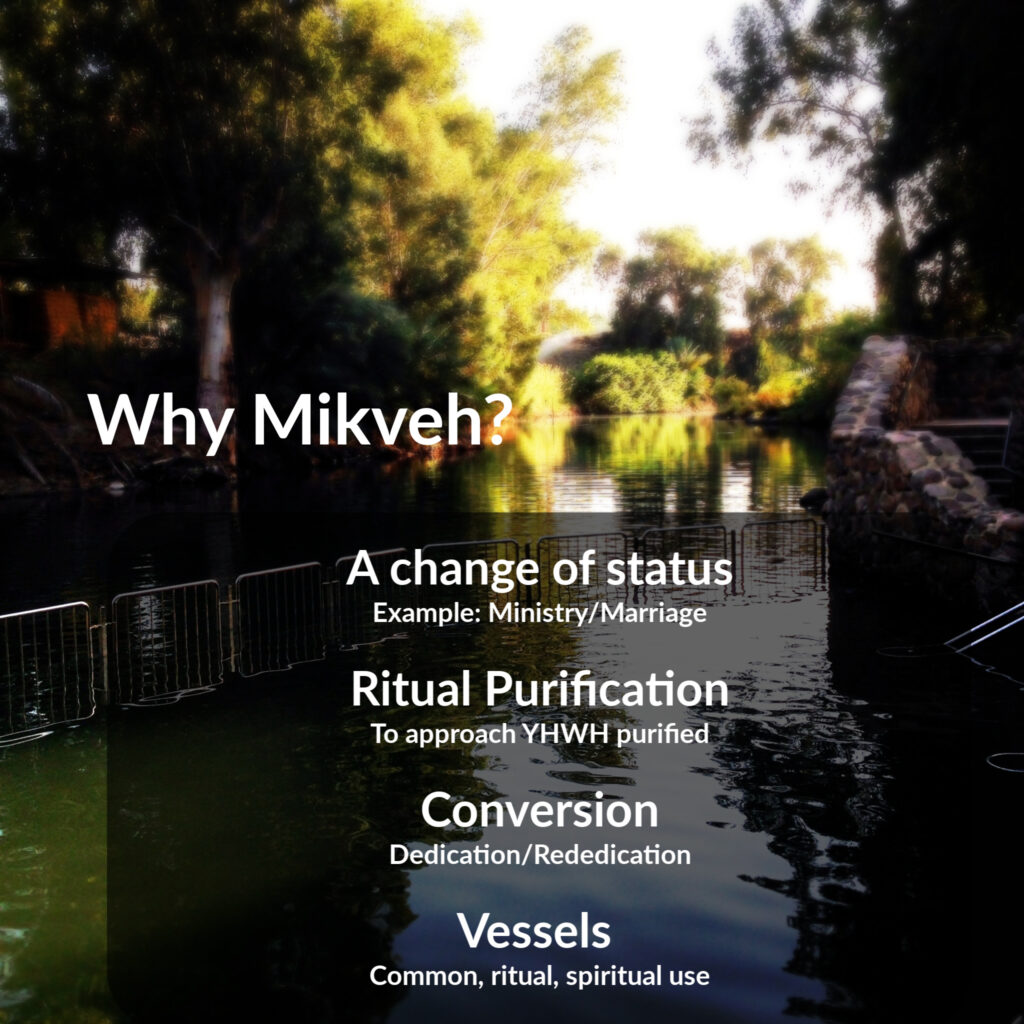

Mikveh is the forefather of what we know as baptism. It is a full immersion or “T’vilah” in water by an individual alone under the supervision of another but without any “help” except for accountability to insure total immersion. Mikveh is a noun which has become a verb through use. We “t’vilah” in a “mikveh”. But now we call the whole experience mikveh and I’ll keep that going for easier communication.

Why mikveh? When mikveh?

Basically the first rule of thumb is to mikveh anytime there is a change of status.

Moses was told to “consecrate the sons of Aaron into the service of the priesthood” and these men, when their status changed, were required to be immersed.

Leviticus 16:1-4, as Moses is given the parameters of how to approach YHVH in the tabernacle. In verse 4, the priest is told to dress in linen and to bathe his body in water before wearing them.

In particular, the priest would mikveh before Yom Kippur. According to tradition, he would immerse and change clothes five times beginning and ending with the golden garments.

Mikveh is also used for “Niddah” or ritual purification. There are actions or behaviors as well as body functions specified in Torah which would cause a person to become ritually unclean (Tumah) and then actions which can be taken to become ritually clean (Tahor). Those commandments are directly related to when or how someone is allowed to enter the temple or not based on their level of spiritual cleanliness. The temple no longer exists and these commands do not apply to gatherings or synagogues. In one area, however, they speak specifically to personal hygiene for women. Leviticus 15:9

The third reason for mikveh is for conversion and by that, I mean all those who turn from sin, who come out of idolatry and polytheism to the embrace of the One and only true Elohim. This is not a process of turning non-jews into jews or attaining a special status.

Biblically, all nations and peoples, including Israel, are to demonstrate “conversion” through mikveh. Yeshua said for us to “repent and be baptized” and following that mandate has become integral to the expression of conversion universally in the Body of Messiah.

In Deuteronomy 29:10-17 God tells the people who they are, who is expected to stand before Him, and what they have been saved from. In Exodus 19:10 he says they should wash their clothing which also implies in the original text that they should wash their bodies as well.

In relation to conversion, mikveh is also often used as a symbol of the rededication of one’s life to Adonai and a reflection of a renewed commitment to follow Him.

Symbolically, mikveh can be related to the crossing of the Red Sea. In the B’rit Hadashah (New Testament) I Corinthians 10:1 reminds us of the crossing through the sea and how they “immersed” themselves into Moses. Which of course, refers to their transformation into a people of the Torah.

The final area where the term mikveh is used is in regards to pots and dishes in relation to their use in Jewish community. It has largely lost its biblically intended purpose for temple vessels and is mainly used in Orthodox households. Numbers 31:21 speaks to the purification of those temple utensils and vessels and the following purification and washing of those who were in charge of that task so that they might participate in tabernacle worship.

In addition to the very physical aspect of clean dishes, I can’t help but also think about 2 Corinthians 4:7 and how we are “earthen vessels” holding the treasures of the Lord. The New Living Translation says it beautifully “We now have this light shining in our hearts, but we ourselves are like fragile clay jars containing this great treasure. This makes it clear that our great power is from God, not from ourselves.”

We wouldn’t only wash a plate once and consider it always clean, would we? Why would we have any different need for short accounts and maintaining a continual posture of cleanliness manifested by an external expression such as mikveh? Not for salvation, not for redemption, not for sanctification. As a reminder of our need to be continually washed and renewed by our Heavenly Father.

As a believer and follower of Yeshua, mikveh is a symbol of our submission to Messiah and our commitment to love and obey Him. It is a beautiful public demonstration of a change in status, a desire to be purified, and a fresh start. The initial moment of declaration when we made a public profession of our rejection of the ways of the world and have embraced Yeshua and His ways, whenever that occurred in our walk of faith, is not the only time we can take advantage of being washed, of making a public declaration, and of making ourselves ready to approach our Abba with joy and confidence.

Teshuvah. Returning to our Father and repenting of the ways of sin and brokenness that the Ruach reveals to us.

Tashlich. Casting our sin away from us and declaring His mercy and goodness.

Mikveh. Being washed clean, made ready for service, publicly rededicating ourselves to Him and to His service.

Two strong biblically supported practices and one simple tradition that bring us to the Days of Awe leading us to the Holiest day of the year, Yom Kippur. Our wedding day. The day of At One Ment.